The world is celebrating the amazing journey that Apollo 11 made to the Moon 40 years ago. But few realise that an early bid to reach the Moon was launched from England, way back in the 17th century.

Incredible as it may seem, one of the greatest scientific minds of the time, Dr John Wilkins, a founder of the Royal Society, was planning his own lunar mission four centuries ago around the time of the English Civil War.

It wasn’t hot air either. Inspired by the great voyages of discovery around the globe by Columbus, Drake and Magellan, Dr Wilkins imagined that it would just be another small step to reach the Moon.

Wilkins, who was a brother-in-law of Oliver Cromwell, explored the possibilities in two books. Records show he began exploring prototypes for spaceships, or flying chariots as he called them, to carry the astronauts.

The Jacobean space programme, as Oxford science historian Dr Allan Chapman calls it, flourished because this was a golden period for science. Huge discoveries had been made in geography, astronomy and anatomy. Seventeenth century scientists were riding a wave.

Galileo’s observations through the telescope had helped show that ancient ideas about the universe were wrong. The Moon’s surface seemed similar to the landscape here on Earth. There were mountains, vast plains, and what they called pits and we call craters.

A Welsh astronomer, using one of the first simple telescopes made for Galileo’s English contemporary Thomas Harriot, reported that lunar features resembled the bays and headlands shown on Dutch sea charts.

Wilkiins was born in 1614, near Northampton, the son of a goldsmith. He graduated from Magdalen College at the age of 17 when he became a teacher and then a clergyman.

His creativity showed itself with inventions such as the first airgun and mileage recorder. He built an artificial rainbow machine to entertain guests in his garden and an inflatable bladder – a prototype for the pneumatic tyre.

Wilkins was inspired by the greatest planetary scientist then known, Johannes Kepler, who had worked out the physical laws governing how planets orbit the Sun. Kepler wrote a book in 1634, an early example of science fiction, imagining how he might be carried to the Moon.

In 1638, when he was just 24, Wilkins produced a new book, The Discovery of a New World in the Moone. He shared the then popular view that other planets and the Moon must be inhabited. He wanted to meet the Selenites as he named them, and even trade with them just as people did with the inhabitants of far flung continents.

He wrote: “In the first ages of the world the Islanders either thought themselves to be the onely dwellers upon the earth, or else if there were any other, yet they could not possibly conceive how they might have any commerce with them, being severed by the deepe and broad Sea.

“But the after-times found out the invention of ships, in which notwithstanding none but some bold daring men durst venture, there being few so resolute as to commit themselves unto the vaste Ocean, and yet now how easie a thing is this, even to a timorous and cowardly nature?

“So, perhaps, there may be some other meanes invented for a conveyance to the Moone, and though it may seeme a terrible and impossible thing ever to passe through the vaste spaces of the aire, yet no question there would bee some men who durst venture this as well as the other.”

Wilkins, pictured right in an engraving, had to consider the problem of escaping our own planet at a time that was still many years before a falling apple led Isaac Newton to identify the force of gravity.

Wilkins, pictured right in an engraving, had to consider the problem of escaping our own planet at a time that was still many years before a falling apple led Isaac Newton to identify the force of gravity.

Instead, Wilkins believed that we were held on Earth by a form of magnetism. His observations of clouds suggested to him that if man could reach an altitude of just 20 miles, he could be free of this force and be able to fly through space.

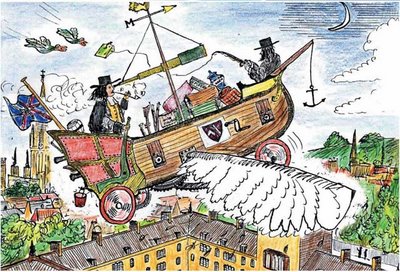

He was fascinated by mechanical devices, clockwork and springs. His big idea was to build a real “spaceship” a flying machine designed like a ship but with a powerful spring, clockwork gears plus a set of wings. Gunpowder could be used for a primitive form of internal combustion engine.

These wings needed to be covered with feathers from high-flying birds such as swans or geese, Wilkins said, and the craft should take off at a low angle – just as modern aircraft do today.

He suggested that ten or 20 men could club together, spending say 20 guineas each, to employ a good blacksmith to assemble such a flying machine from a set of plans.

Today’s astronauts take special space food prepared for a weightless environment. Wilkins believed food would not be needed by his explorers. He thought there was already evidence of people going long periods without eating. And in space, free of Earth’s “magnetism”, there would be no pull on their digestive organs to make them hungry, he argued

Similarly, breathing would not be a problem. It was known that mountaineers suffered breathlessness at high altitude. Wilkins said this was because their lungs were not used to breathing the pure air breathed by angels. In time his astronauts would get used to it and so be able to breathe on their voyage to the Moon.

Records show that Wilkins did experiment in building flying machines with another leading scientist of the age, Robert Hooke, in the gardens of Wadham College, Oxford, around 1654. But by the 1660s, he began to realise that space travel was not as straightforward as he had imagined.

Dr Chapman, of Wadham College, Oxford, is in no doubt that Wilkins is the father of the space programme. He told Skymania News: “Definitely. No doubt about it. His ingenuity was enormous. He saw his flying chariot as being the space version of Drake’s, Raleigh’s and Magellan’s ships.

“In the same way that it was an Englishman, Thomas Harriott, who beat Galileo in using the telescope, so on the 40th anniversary of the landing on the Moon it was an Englishman who came up with the best argued possibility of getting to the Moon in his day.

“This was a honeymoon period of British science. The vacuum had not yet been discovered. In 1640, flying to the Moon was a heroic possibility.

“But by 1670, they realised it was impossible. They’d made so many discoveries in physics and astronomy in 30 years that they could see that flying to the Moon was not on. But in that glorious period around 1640, it seemed a real possibility.”

Picture: This humorous illustration imagining Wilkins’ flying chariot is by Allan Chapman and reproduced with his permission. It shows Wilkins and Hooke on their journey from Oxford to the Moon.